Robotics has evolved from myth and mechanical curiosities into a vast, cutting-edge field impacting nearly every industry today. The concept of artificial helpers and automatons dates back millennia, while modern robotics emerged with the advent of electronics and computing in the 20th century. This report provides a global overview of robotics history, highlighting key technological eras, influential figures, major milestones, and future trends in AI-driven robotics across industries.

Early Innovations: From Mythical Automata to the Industrial Age

The idea of artificial humanoids and self-moving machines is ancient. In Greek mythology of the 8th century BCE, Homer imagined mechanical servants: golden handmaidens built by Hephaestus that could move and speak, and the bronze giant Talos that guarded Crete. Such legends demonstrate that thousands of years before the word “robot” was coined, people conceived of lifelike automata serving human masters. By the Hellenistic period (3rd–1st centuries BCE), engineers in Alexandria (like Ctesibius and Heron) were actually designing primitive automated machines. They created water-powered mechanical birds, puppets, and temple doors, illustrating physical principles with moving figures driven by steam, air, and hydraulics. Similar tales of mechanical guardians appear in ancient Indian and Chinese texts as well, suggesting a cross-cultural fascination with automata even in antiquity.

Medieval and Renaissance engineers carried forward this automaton tradition. In the Islamic Golden Age, Ismail al-Jazari (1136–1206) designed remarkable water clocks, musical robots, and automated servants that poured drinks or presented towels to guests. His 1206 manuscript The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices detailed over a hundred inventions, laying “groundwork for modern engineering, hydraulics, and even robotics”. In Renaissance Europe, polymath Leonardo da Vinci sketched plans for a mechanical knight (circa 1495) that could sit up, move its arms, and even open its visor – an invention five centuries ahead of its time. European clockmakers and craftsmen later built sophisticated automatons: for example, Jacques de Vaucanson’s famous digesting duck (1739) and Pierre Jaquet-Droz’s writing doll (1770s) amazed audiences by mimicking life. These creations, while not programmable in the modern sense, demonstrated complex mechanical control and inspired generations of inventors.

By the Industrial Revolution, engineering advances enabled practical automation of labor. An important milestone was the Jacquard loom (1804) invented by Joseph-Marie Jacquard, which used punched cards to automatically weave complex patterns. This loom is regarded as the first machine to automatically execute a sequence of operations, making mass production of intricate textiles possible. The Jacquard system directly influenced later computing and control technologies, foreshadowing how machines could be “programmed” – a concept central to robotics. By the late 19th century, inventors were experimenting with remote and electrical control of machines: for instance, Nikola Tesla demonstrated a radio-controlled boat in 1898, hinting at the potential for wireless tele-operated robots. As the new century dawned, the cultural idea of the “robot” was about to be born in literature even before real robots existed.

In 1920, the term “robot” entered the lexicon via Czech writer Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). Čapek’s “robots” were artificial factory workers – the word came from robota, meaning forced labor. This play captured imaginations worldwide and set the stage for thinking about machines as workers or even intelligent beings. Two decades later, science-fiction author Isaac Asimov not only popularized robots in fiction but also introduced the term “robotics” (first used in his 1941 story Liar!). Asimov also proposed ethical guidelines in his “Three Laws of Robotics” (1942), anticipating the social and technical challenges of intelligent robots. Thus, long before real robots were common, the early 20th century defined the concept of a robot and its role – an autonomous machine servant – in both industry and imagination.

The Dawn of Modern Robotics in the 20th Century

True modern robotics began with the convergence of electronics, control systems, and computing in the mid-20th century. One pioneering effort came in the late 1940s when British neurophysiologist William Grey Walter built a pair of autonomous electro-mechanical robots named “Elmer” and “Elsie.” These turtle-like robots (1948–49) could sense light and touch, navigate around obstacles, and find their charging stations – making them the first electronic autonomous robots in history. Grey Walter’s “tortoises” were simple by today’s standards, but they proved that rudimentary sensors and circuitry could yield lifelike, adaptive behavior, influencing the new field of cybernetics.

The first industrial robot soon followed. American inventor George Devol created the earliest programmable robotic arm in 1954 and partnered with engineer Joseph Engelberger to found Unimation, the world’s first robotics company. Their invention, the Unimate, was an electronically controlled hydraulic arm designed to perform repetitive or dangerous tasks in factories. After a prototype was tested at a General Motors plant in 1959, the Unimate became the first robotic machine to work on a factory assembly line in 1961 at a GM plant in New Jersey. There, it tirelessly lifted and stacked hot metal parts, a job considered dirty and hazardous for humans. This milestone marked the dawn of the robotics industry, proving that robots could improve productivity and safety in industrial settings. By the late 1960s, companies in the U.S. and Europe were developing their own industrial robots, and Unimate robots were even exported to Japan, planting the seeds of a global robotics revolution.

At the same time, robotics research labs were tackling the challenge of robotic intelligence and autonomy. A landmark project was “Shakey”, developed from 1966 to 1972 at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in California. Shakey was a wheeled robot outfitted with a camera, sensors, and a computer brain. It could perceive its environment, navigate rooms, and perform simple problem-solving – the first mobile robot that could reason about its actions rather than just repeat pre-programmed routines. Shakey’s ability to plan steps and adjust to its surroundings (albeit slowly) earned it fame as the world’s first AI-based robot, demonstrating the powerful combination of robotics and artificial intelligence. This breakthrough inspired countless future technologies, from the Roomba vacuum to self-driving cars, as noted by its creators. By the end of the 1960s, the foundation of modern robotics was in place: robots existed that could sense, compute, and act.

The 1970s and 1980s saw rapid advances and worldwide adoption. In 1970, Japan launched its first industrial robot (a Unimate installed by Kawasaki Heavy Industries) and subsequently invested heavily in robotics. Japanese researchers also pushed the envelope in humanoid robotics – notably Waseda University’s WABOT-1 (1973), which was the world’s first full-scale anthropomorphic robot. WABOT-1 could walk, grip objects, see via cameras, and carry on basic conversations, an astonishing leap for the era. Its development, led by Professor Ichiro Kato, integrated key technologies (limb control, vision, and speech) into one human-sized machine. Meanwhile, industrial robotics became a cornerstone of manufacturing. By 1980, Japan had become the world’s top automobile producer and began deploying robots widely in car factories. This was accelerated by the need for efficiency and a shortage of skilled labor. Japanese companies like Fanuc, Yaskawa, and Mitsubishi competed fiercely to improve robot performance, and by the mid-1980s Japan emerged as the global leader in both robot production and use. Similar growth occurred in Western Europe and the U.S., albeit at a slower pace. Robots took on welding, painting, assembly, and packaging tasks, transforming industrial workflows. In 1978, a collaboration between academia and industry produced the PUMA robot arm (Programmable Universal Machine for Assembly), designed by Victor Scheinman at Stanford and commercialized by Unimation/GM. The PUMA introduced a new level of precision with its electric motors and six-axis articulation, and it became a standard model for light assembly tasks by the 1980s.

Beyond the factory floor, robots were also venturing into hazardous and remote environments. A crowning achievement of the Soviet space program was Lunokhod 1, the world’s first planetary exploration rover. In November 1970, the USSR landed Lunokhod 1 on the Moon – a bathtub-shaped robot on wheels that roamed the lunar surface for 11 months. Lunokhod was driven remotely from Earth, sending back images and data, and proved the value of robotic explorers in space. This success paved the way for NASA’s Mars rovers decades later. Back on Earth, robotic vehicles and manipulators were being used in nuclear power plants, undersea exploration, and military applications (for example, rudimentary drone aircraft and bomb-disposal robots appeared by the 1980s). By the end of the 20th century, robotics had expanded far beyond its industrial origins – from laboratories to factory floors, from oceans to outer space – reflecting a truly global effort. The stage was set for robots to enter daily life.

Robotics in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries

The 1990s and early 2000s witnessed robotics technology mature and diversify dramatically. Industrial robots grew more intelligent and easier to integrate, thanks to advances in computing, sensors, and networking. Europe and North America joined Asia in heavily utilizing robots for manufacturing, and new sectors like electronics assembly and food processing began to automate with robotics. In 2000, the global installed base of industrial robots was roughly half a million units; two decades later it would exceed three million, illustrating the exponential growth of automation worldwide. Japan continued to innovate in humanoids, unveiling Honda’s ASIMO in 2000 – a child-sized bipedal robot capable of climbing stairs and responding to voice commands, representing one of the most advanced humanoids of its time.

Crucially, robots also started to enter the consumer and service realms. In 1999, Sony introduced the AIBO robotic dog, an entertainment robot pet with rudimentary AI, which became a status symbol and testbed for human-robot interaction. Affordable home robots truly arrived in 2002, when iRobot (a spin-off from MIT) launched the Roomba – a small autonomous vacuum cleaner that became the first commercially successful home robot, selling millions of units worldwide. For the first time, ordinary people could have a robot help with household chores. This era also saw the rise of robotic prosthetics and medical devices like the da Vinci Surgical System (FDA-approved in 2000), which allowed surgeons to perform delicate operations via robotic arms – effectively a human-controlled robot extending surgical precision. In space, NASA’s Sojourner rover trundled across Mars in 1997, proving that robotic explorers can perform effectively on other planets and laying groundwork for the sophisticated Mars rovers (Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, Perseverance) of the 2000s and 2010s.

Another significant trend was the development of autonomous vehicles and drones. Spurred by the DARPA Grand Challenges (2004–2007) for self-driving cars, rapid progress in sensors (like LIDAR) and AI led tech companies and automakers to invest heavily in autonomy. By the mid-2010s, experimental self-driving cars were navigating city streets, and companies were piloting robotic delivery drones and warehouse robots. For instance, Amazon’s acquisition of Kiva Systems in 2012 brought fleets of autonomous mobile robots into e-commerce warehouses, revolutionizing logistics. Dynamic legged robots also made headlines – Massachusetts-based Boston Dynamics (founded by Marc Raibert) developed quadrupedal and bipedal robots with astonishing capabilities. Videos of their “BigDog” (a sturdy four-legged robot funded by DARPA) navigating rough terrain in 2004, and later of the humanoid Atlas robot executing backflips (2017), went viral, exemplifying cutting-edge engineering. By the early 2020s, robots were not only stronger and more precise, but also noticeably “smarter” – thanks to the incorporation of AI techniques like machine vision and deep learning for recognition and decision-making.

Globally, robotics became a strategic priority. Countries like South Korea and Germany achieved some of the highest robot densities in manufacturing. China emerged in the 2010s as both the largest market for industrial robots and an increasingly significant producer – its government investing heavily in automation to upgrade factories and address labor shortages. Startups and research labs worldwide pushed the envelope in specialized areas: search-and-rescue robots, agricultural robots (from milking machines to crop-monitoring drones), and social robots for communication and care. By 2025, robotics had truly come of age, moving well beyond the factory cage into our homes, hospitals, skies, and beyond. The rich history of innovations and milestones from every corner of the globe set the foundation for the future of robotics, intertwined with advancements in artificial intelligence.

Pioneers and Innovators in Robotics History

The evolution of robotics has been driven by visionary inventors, engineers, and thinkers across different eras and regions. Early inspirations can be traced to figures like Archytas of Tarentum, a Greek scholar said to have built a mechanical flying pigeon in the 4th century BCE, and Heron of Alexandria, who in the 1st century CE documented how to construct self-moving devices including theatrical automata and even a primitive steam engine. These ancient pioneers provided the earliest blueprints for automating motion. In the medieval Islamic world, Al-Jazari stands out – his ingenious 12th-century designs of clocks and automata (humanoid servants, water-powered peacocks, etc.) earned him the moniker “father of robotics” in some historical accounts. By documenting his inventions in detail, al-Jazari bridged craftsmanship and engineering science, influencing both Eastern and Western inventors.

In the modern era, the concept of the robot owes much to Karel Čapek and Isaac Asimov. Čapek, though a writer and not an engineer, introduced the world to the term robot in 1920, sparking imaginations about mechanical laborers and the ethical implications of creating life-like machines. Asimov, through his 1940s stories, anticipated the field of “robotics” and put forward the Three Laws of Robotics as a framework for safe human-robot interaction. Their ideas influenced real roboticists to consider not just how to build robots, but also how robots should behave.

The practical realization of robots came from inventors like George Devol and Joseph Engelberger. Devol’s 1954 patent for a “programmable article transfer” device led directly to the Unimate, and Engelberger – often called the “father of industrial robotics” – brought that invention to market, installing the first robot arm at a GM plant in 1961. Together, they showed how entrepreneurship and innovation could turn science fiction into industrial reality. In parallel, William Grey Walter’s work on autonomous “tortoise” robots (1948) made him a founding figure of cybernetics and behavior-based robotics, demonstrating that simple electronic brains could give rise to complex actions. His experiments influenced later researchers like Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy, who in the 1950s and ’60s founded artificial intelligence labs (at MIT and Stanford) that treated robotics as a key testbed for AI.

Another giant of 20th-century robotics research is Charles Rosen, who led the SRI team that created Shakey. Together with colleagues Nils Nilsson, Bertram Raphael, and others, Rosen pursued the bold idea of an autonomous robot that could perceive and plan – effectively birthing the field of mobile robotics and robotic AI. Shakey’s success in 1972 (and its subsequent IEEE milestone award) is a testament to their vision. In academia, Victor Scheinman revolutionized robot manipulators by inventing the all-electric, computer-controlled Stanford Arm (1969) and later the PUMA robot, enabling fine robotic motion that benefited both factories and research. Another influential figure, Masahiro Mori in Japan, contributed more on the theoretical side: in 1970 he proposed the famous “uncanny valley” hypothesis, describing how people feel revulsion as a robot’s appearance becomes almost – but not fully – human. Mori’s insight guided robot designers to consider aesthetics and psychology, not just engineering.

From the 1980s onward, the robotics field expanded, and so did its roster of innovators. Ichiro Kato in Japan deserves credit for spearheading humanoid robotics with WABOT-1 and mentoring a generation of Japanese roboticists in human-machine interaction. In the West, Rodney Brooks (an Australian-American roboticist at MIT) challenged conventional AI approaches with his 1986 paper “Intelligence Without Representation,” advocating for robots that learn from embodied experience rather than extensive programming. Brooks went on to co-found iRobot (bringing robots into homes) and Rethink Robotics (pioneering collaborative factory robots), making a lasting impact on both theory and industry. Mark Raibert, initially an academic at Carnegie Mellon and MIT, later founded Boston Dynamics and advanced the art of legged locomotion. His team’s prototypes showed that robots could run, jump, and balance dynamically, which was long thought too hard for machines. In Europe, figures like Bruno Siciliano and Oussama Khatib contributed influential research in robot control and safety, while KUKA’s founders (Johann Keller and Jakob Knappich in Germany) were instrumental in developing industrial robot arms in the 1970s, spreading their use in European manufacturing.

It’s also important to acknowledge innovators in emerging areas: Hiroshi Ishiguro in Japan gained fame for ultra-realistic androids that explore the boundaries of human-likeness; Cynthia Breazeal at MIT created some of the first social robots (such as the expressive robot head Kismet) and has been a leader in personal robotics and education. And in the realm of space robotics, engineers like Vladimir Bugrov (designer of Lunokhod) and William “Red” Whittaker (who built early autonomous planetary rovers and mining robots at CMU) have pushed robots into the final frontier. These and many other individuals around the world collectively advanced robotics through their inventions and ideas. Robotics, as a field, stands on the shoulders of such pioneers – a blend of dreamers and doers who turned imaginative concepts into tangible machines.

Future Outlook: AI and Robotics in Society

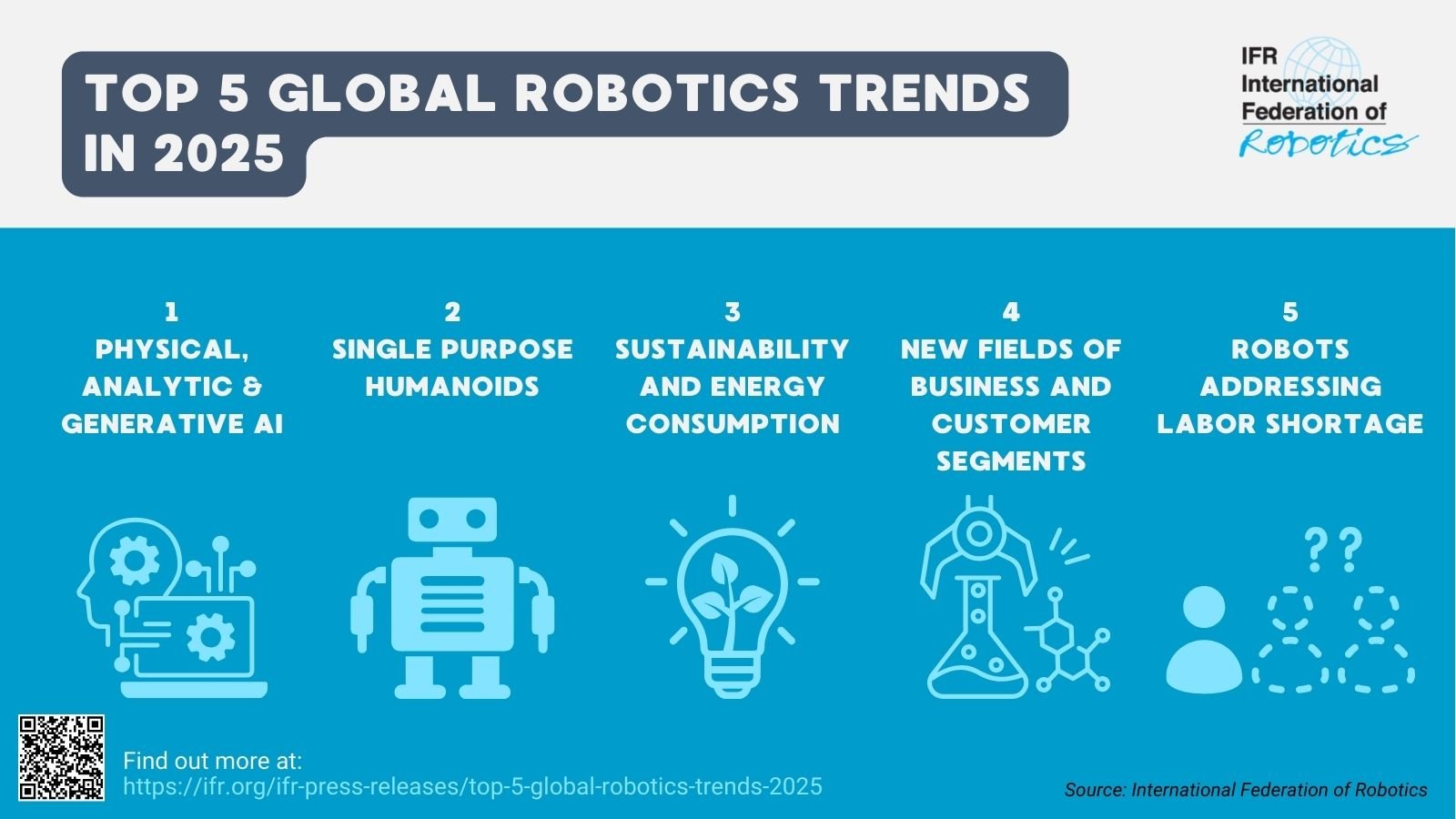

As we look ahead, robotics and artificial intelligence are converging to produce even more capable and ubiquitous robots. Future robots will increasingly perceive, learn, and reason thanks to AI, enabling them to perform complex tasks in unstructured environments. The coming decades promise transformative applications across a broad spectrum of industries and aspects of daily life. Below, we explore several key domains where robotic innovation – enhanced by AI – is driving the future.

Healthcare and Medicine

In healthcare, robots are poised to become indispensable partners to doctors, nurses, and caregivers. Surgical robots are already well established – the next generation will incorporate more AI to provide decision support during operations, improve dexterity, and even perform simple procedures autonomously under supervision. Hospitals are deploying robots for routine tasks such as transporting medicines and linens, disinfecting rooms with UV light, and assisting with patient rehabilitation exercises. In elder care, socially assistive robots and “care-bots” are being tested to help the elderly or disabled with daily activities and to provide companionship. Thanks to AI, these robots can monitor vital signs, detect falls or emergencies, and learn an individual’s habits to offer personalized support. The synergy of AI and robotics is also accelerating medical research and diagnosis – for example, robotic lab systems can test thousands of samples around the clock, and AI algorithms enable them to detect anomalies or diseases in medical images. In the coming years, we may see robotic systems that perform ultrasound scans, draw blood, or even assist in surgeries remotely via telepresence. Such developments could greatly expand access to quality healthcare. Indeed, a recent review notes that the future of AI-driven robots in healthcare spans everything from elderly care and remote patient monitoring to drug discovery and epidemic outbreak prediction. Challenges remain (regulatory approval, patient trust, integration into clinical workflows), but the overall trajectory points to robots playing a vital role in making healthcare more efficient, safe, and accessible.

Manufacturing and Industry

Factories of the future will be smart, flexible and heavily automated. Building on the foundations of today’s Industry 4.0 movement, industrial robots will become even more autonomous and collaborative. AI enables robots to adapt to variations in materials and product designs on the fly, which means production lines will be able to handle a high mix of products without extensive reprogramming. Moreover, robots are learning to work safely alongside human workers as cobots (collaborative robots) – agile robotic arms equipped with vision and force sensors that allow them to literally share a workspace with people. This opens up automation to small and medium-sized enterprises that do assembly or packaging, where full automation was previously too costly or inflexible. New business models like Robot-as-a-Service are lowering barriers to entry by letting companies “rent” robotic automation as needed, rather than purchase expensive machines upfront.

In addition, AI-powered predictive maintenance will keep factory robots up and running with minimal downtime, as the machines themselves will detect wear or faults before they cause failures. Logistics and warehousing is another booming area: fleets of mobile robots carry and sort goods in giant fulfillment centers, guided by AI path-planning algorithms. By 2025, it’s expected that professional service robots (like logistics, retail, and warehouse robots) will outnumber traditional industrial robots, reflecting the expansion of automation beyond traditional manufacturing. The role of human workers will shift to managing, programming, and maintaining robots – essentially supervising automated processes. This also ties into broader economic factors: in countries facing aging workforces and labor shortages (from Japan to Germany), robots are increasingly seen as crucial to fill the gaps. In sum, manufacturing will likely achieve levels of efficiency and output previously unattainable, by leveraging intelligent robotics that can operate 24/7, minimize waste, and ensure consistently high quality. The concept of “dark factories” (fully automated facilities with lights off) might become reality in some sectors, although in many cases humans will still work in tandem with robots for tasks that benefit from human judgment or flexibility.

Transportation and Mobility

Perhaps no field has captured the public imagination for future robotics as much as autonomous transportation. Self-driving cars, taxis, trucks, and buses are under intensive development by automakers and tech companies around the world. With continuing advances, autonomous vehicles (AVs) promise to reduce accidents (most of which are due to human error), improve traffic flow, and provide mobility to people unable to drive – such as the elderly or disabled. By using AI to perceive road conditions and make split-second decisions, AVs could eventually transform our roads and cities. Pilot programs of robo-taxis and autonomous shuttles are already running in cities from California to Beijing, though widespread adoption may take another decade or more to resolve technical and regulatory hurdles. In the meantime, driver-assist features are progressively adding more autonomy to human-driven cars (adaptive cruise control, lane keeping, automatic emergency braking), gradually building trust in robotic driving systems.

Beyond passenger vehicles, robotics is revolutionizing logistics and delivery. Autonomous drones are being tested to carry packages to customers’ doorsteps – for example, delivering medicine to remote areas or e-commerce orders to homes. Ground delivery robots, which are essentially small self-driving boxes on wheels, are rolling along sidewalks in some cities delivering food and groceries. In warehouses and ports, AI-guided cranes and trucks move shipping containers and pallets with minimal human intervention. The airline industry, too, is exploring autonomous technology: experimental “flying taxis” (multirotor drones large enough to carry people) might become a reality in urban centers, and aircraft manufacturers are looking at robotic co-pilots and eventually pilotless commercial flights (though public acceptance for the latter is a big hurdle). Traffic management will also benefit from AI and robotics – smart traffic lights that respond to real-time conditions, drone networks monitoring and easing congestion, and platoons of autonomous trucks on highways moving in tightly coordinated convoys to save fuel.

The convergence of connectivity (5G networks), AI, and robotics in transportation could yield a future with fewer emissions and more efficient mobility. However, as the World Economic Forum cautions, simply replacing every car with a self-driving version won’t automatically solve problems like congestion. The optimal future may involve integrating autonomous vehicles with public transit and reshaping city infrastructure. Still, it’s clear that robots will play a central role in how we move people and goods, from autonomous ride-sharing cars to drone deliveries and beyond.

Home and Daily Life

In daily life, robots are set to become as common in the 21st century as household appliances were in the 20th. We have already seen the acceptance of simple home robots like the Roomba vacuum. The next wave of home automation robots will be smarter and more capable. Research labs and startups are working on robotic assistants that can help with household chores – for example, robots that can tidy up toys, load and unload dishwashers, fold laundry, or prepare simple meals. These tasks, which require dexterity and recognition of a wide variety of objects, are extremely challenging for AI and robotics, but rapid progress in machine vision and manipulation is bringing them closer to reality. Tech visionaries are imagining a general-purpose home robot – essentially a mobile manipulator that could navigate through your house and handle a range of domestic tasks on demand. Several startups (in Silicon Valley, Japan, and elsewhere) have unveiled humanoid or animal-like prototype robots intended for home use, though none have yet reached mass market.

One prominent focus is on humanoid robots for general use. Humanoids have the advantage of being able to operate in environments designed for humans (climbing stairs, turning knobs, using tools). Companies are actively developing humanoid robots that might act as butlers or helpers. For instance, some prototypes aim to load the dishwasher, then head to a factory and work on an assembly line – a vision of robots that can learn many tasks rather than being fixed to one job. While the grand vision is still on the horizon, simpler single-purpose humanoids are likely to emerge first (for example, a robotic concierge that greets visitors and carries luggage, or a warehouse humanoid that lifts boxes). Outside of work, personal companion robots may offer emotional support or entertainment. Japan has been a leader in this area, with products like SoftBank’s Pepper, a friendly humanoid that can converse and dance, used in some shops, eldercare homes, and schools. As populations age, particularly in East Asia and Europe, such companion robots might help alleviate loneliness and assist with monitoring health and wellness.

In the smart home ecosystem, robots will integrate with IoT (Internet of Things) devices. Imagine your home security drone patrolling at night, or a window-cleaning robot that comes out when sensors detect the glass is dirty. There are also telepresence robots – essentially mobile video conferencing units – that let people be “virtually present” in another location (these saw a surge of interest during the COVID-19 pandemic for remote hospital visits and work meetings). Over the next decade, as AI makes robots more context-aware and user-friendly, we can expect a proliferation of gadgets that blur the line between appliance and robot. From robotic lawn mowers to pool cleaners to interactive toys that teach children, these machines will handle mundane tasks and provide new forms of home convenience and entertainment. One challenge will be ensuring they are easy to use and affordable; another is designing them to be safe to operate around children and pets. But given the fast pace of innovation, the once-fanciful idea of a home with its own robot helper is quickly moving from science fiction to an approachable reality.

Space Exploration

Space is the ultimate frontier where robots have already proven their worth – and future missions will rely even more on robotic explorers and workers. Every planetary rover or space probe is essentially a robot, and AI advances will make them more autonomous, allowing them to travel farther and make smart decisions without waiting for commands from Earth. NASA and other agencies plan increasingly ambitious rover missions (to the Moon, Mars, and even asteroids) in the 2020s and 2030s. For example, NASA’s upcoming VIPER rover will search for water ice at the Moon’s south pole, and Europe’s Rosalind Franklin rover will drill into Martian soil – these robots operate with minimal human guidance due to long communication delays. Humanoid or legged robots may join future lunar missions to assist astronauts in construction and maintenance of lunar bases, performing tasks in environments that are risky for humans (extreme temperatures, radiation, vacuum). Japan’s space agency JAXA has tested small humanoid “astronaut” robots on the International Space Station (the robot crewman CIMON by ESA/DLR and Int-Ball by JAXA are early examples of robots working with human crews in microgravity).

A major emerging field is on-orbit servicing and assembly: using robots to repair satellites, refuel them, or even build structures in orbit. By 2030, it’s estimated that about 34% of space robots will be dedicated to on-orbit servicing, assembly, or manufacturing tasks. This includes robotic arms on spacecraft that can catch and refuel a satellite or replace faulty components, extending its life instead of it becoming space debris. The Canadian-built Dextre robot on the ISS has already demonstrated many maintenance tasks outside the station. Looking ahead, multiple companies (in the U.S., Europe, and China) are developing robotic servicing vehicles, and NASA’s upcoming OSAM-1 mission will use a robotic arm to assemble a functional spacecraft component in orbit. We may even see robotic factories in space that can 3D-print large structures (like antennas or even habitation modules) which would be difficult to launch from Earth. On the Moon and Mars, robotic miners and builders are envisioned to harvest local materials and construct habitats before human arrival. Concepts for robotic swarms – dozens of small robots working in concert – could enable efficient exploration or construction on other planetary surfaces.

In summary, robots will go where it’s too dangerous, expensive, or impractical to send humans. They will augment human space exploration, not only by doing precursor scouting and construction, but also by working side by side with astronauts in future missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond. The continued miniaturization of electronics and improvement in AI means even tiny CubeSat robots can carry significant computing power and act intelligently. As one report notes, the space robotics market is growing quickly, projected to reach over $5 billion by the mid-2020s, driven by the demand for satellite maintenance and debris clean-up. In the long term, autonomous robotic spacecraft might even enable entirely new ventures like asteroid mining, assembling large solar power stations in orbit, or exploring the oceans of distant moons (using submersible robots to probe the waters of Europa or Enceladus). The future of space exploration is inevitably tied to the future of robotics – each new advance in robot capability expands what we can achieve in the cosmos.

Education and Research

Robots are also increasingly finding their way into education, from kindergarten classrooms to university labs. Educational robotics serves two roles: teaching about robotics and AI (to build the future workforce of engineers), and using robots as tools for teaching other subjects. In schools around the world, robots are being used to spark interest in STEM through playful, hands-on learning. Small programmable robots like Lego Mindstorms, VEX robots, or the Dash and Dot robots help children learn coding, problem-solving, and creativity. There are even curricula built around students assembling and programming their own robots, which builds engineering skills in a multidisciplinary way. But beyond STEM, researchers have found that child-friendly robots can tutor students in languages, math, or social skills. For example, SoftBank’s NAO robot has been used in studies as a one-on-one language tutor for young children, giving personalized lessons and engaging kids with interactive dialogues. Because the robot can hold basic conversations and exhibit gestures or emotions (through face and voice), children often find it engaging and non-judgmental, which is especially useful for shy learners or those needing extra help. Early results suggest that robots as teaching assistants can help reinforce material and free up human teachers to focus on more individualized coaching.

In higher education and research, robots play a crucial role in experimentation. Universities use advanced robotics platforms to research fields like human-robot interaction, artificial intelligence algorithms, biomechanics (by studying how robots can mimic animal locomotion), and more. Humanoid robots are being used to study how children with autism respond to social cues, since some non-neurotypical children find interacting with a predictable robot easier than with a human. Telepresence robots enable students who are home-bound (due to illness or disability) to attend classes virtually, moving around and interacting through a robot proxy. There is also a push to incorporate AI tutors in educational software – one can imagine a future where each student has a personalized AI-robot tutor that adapts to their learning pace and style, a concept sometimes called the “robot in every classroom.” While robots won’t replace human teachers (who provide creativity, empathy, and complex understanding), they can certainly augment educational delivery. They might handle repetitive drilling of basics, serve as laboratory assistants, or provide exposure to different languages and cultures by embodying remote instructors (for instance, a language teacher appearing via a robot in a distant classroom).

Crucially, teaching about robotics is becoming as important as teaching with robotics. Governments worldwide (from China to the EU to the U.S.) have invested in robotics education programs, believing that robotics and AI literacy will be essential for future jobs. Competitions like FIRST Robotics and World Robot Olympiad have exploded in popularity, motivating students globally to design their own robots to solve challenges. By 2030, we could see robotics kits as common in schools as chemistry sets, and perhaps a robotics “literacy” – understanding how to work with and alongside robots – as a standard part of education. This will help society adapt to a world where interacting with robots (as coworkers, assistants, or tools) is commonplace.

In conclusion, robotics has traveled a remarkable journey from ancient automata to autonomous machines endowed with artificial intelligence. Its history is rich with creativity and ingenuity from diverse cultures and individuals. Today’s state-of-the-art robots build upon centuries of innovation and decades of rapid technological progress. As we stand on the cusp of robots becoming pervasive in our lives – whether as surgeons, factory workers, drivers, helpers, or explorers – it is clear that the age of robotics has truly begun. The future promises not just more advanced robots, but also deeper integration of these intelligent machines into the fabric of human society, working hand in hand with people to improve our quality of life and expand the horizons of what we can achieve.

Sources:

-

MIT Press Reader – Surveillance, Companionship, and Entertainment: The Ancient History of Intelligent Machines

-

Communications of the ACM – Leonardo da Vinci’s Robots (Herbert Bruderer, 2024)

-

National Geographic History Magazine – Medieval Robots? (Ismail al-Jazari’s inventions)

-

Britannica – “Robot” (technology) definition and history

-

University of Bristol News – Grey Walter’s Tortoises (first autonomous robots)

-

Britannica – Industrial robotics (Unimate and early industry use)

-

SRI International – Meet Shakey the Robot (world’s first AI robot)

-

Waseda University Humanoid Robotics Institute – History of WABOT-1 (first humanoid robot)

-

International Federation of Robotics – Why Japan Leads Industrial Robot Production

-

Space.com – Lunokhod 1: First Successful Lunar Rover

-

Narwal Robotics – History of the Robot Vacuum (Roomba 2002)

-

IFR Press Release (2025) – Top 5 Global Robotics Trends (AI and Humanoids)

-

IFR Press Release (2025) – Robots addressing labor shortages

-

World Economic Forum – Future of Autonomous Vehicles (benefits and challenges)

-

3Laws Robotics – Future of Space Robots (On-orbit services by 2030)

-

BuiltIn – Robotics in Education (roles of robots as tutors/assistants)